Exploratory Data Analysis, Correlations, and Autocorrelations

Lecture 05

February 5, 2024

Last Class(es)

Probability Models

Goal: Write down a probability model for the data-generating process for \(\mathbf{y}\).

- Direct statistical model, \[\mathbf{y} \sim \mathcal{D}(\theta).\]

- Model for the residuals of a numerical model, \[\mathbf{r} = \mathbf{y} - F(\mathbf{x}) \sim \mathcal{D}(\theta).\]

Model Fitting as Maximum Likelihood Estimation

We can interpret fitting a model (reducing error according to some loss or error metric) as maximizing the probability of observing our data from this data generating process.

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

EDA: Assessing Model-Data Fit

Examples:

- Skewness

- Tails

- Clusters

- (Auto)correlations

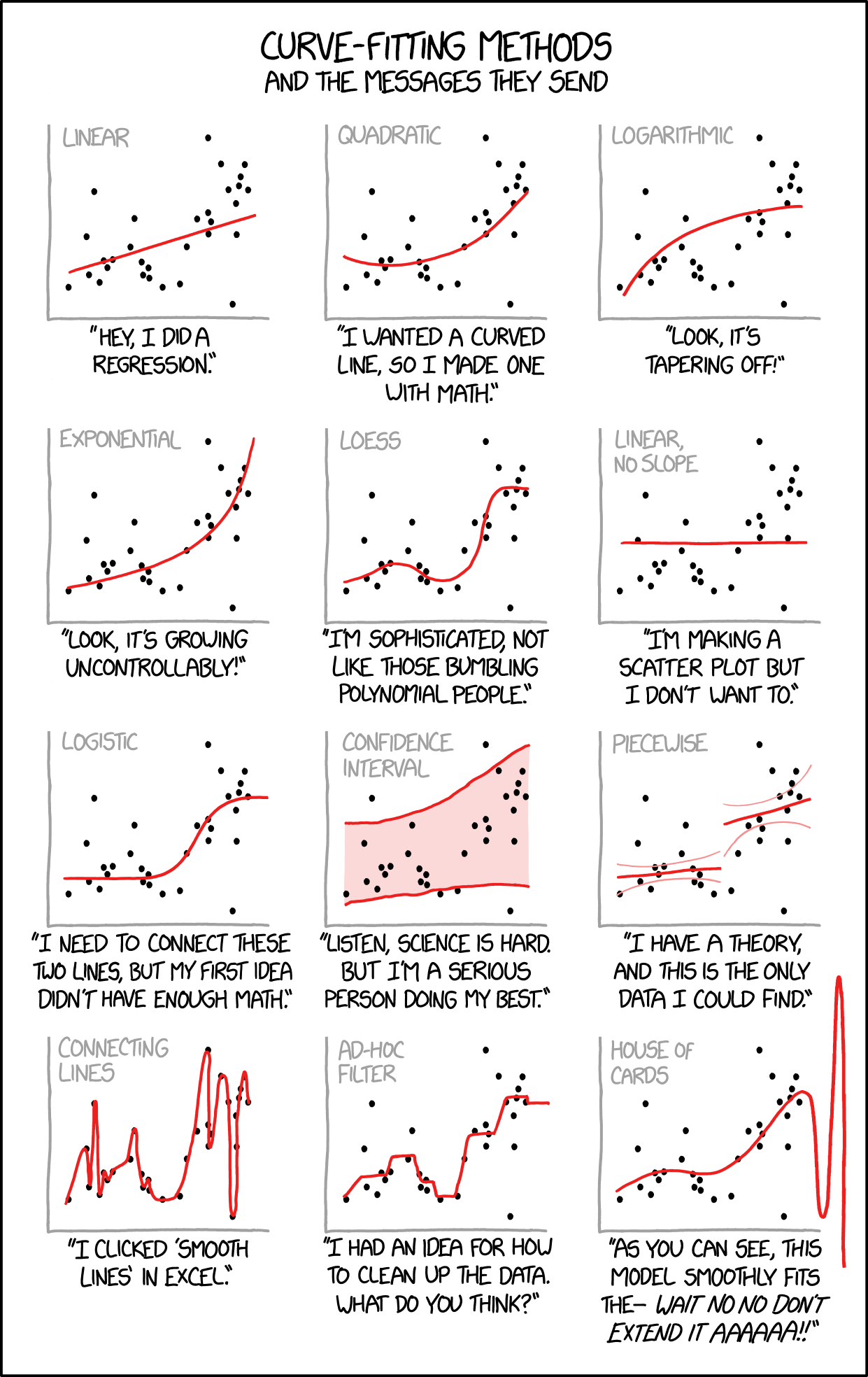

Curve Fitting

Source: XKCD #2048

Is EDA Ever Model-Free?

Some characterize EDA as model-free (versus “confirmatory” data analysis).

Is this right?

Visual Approaches to EDA

Make plots!

- Histograms

- Scatterplots/Pairs plots

- Quantile-Quantile Plots

Skew

Code

# specify regression model

f(x) = 2 + 2 * x

pred = rand(Uniform(0, 10), 20)

trend = f.(pred)

# generate normal residuals

normal_residuals = rand(Normal(0, 3), length(pred))

normal_obs = trend .+ normal_residuals

## generate skewed residuals

skewed_residuals = rand(SkewNormal(0, 3, 2), length(pred))

skewed_obs = trend .+ skewed_residuals

# make plots

# scatterplot of observations

p1 = plot(0:10, f.(0:10), color=:black, label="Trend Line", linewidth=2, guidefontsize=18, tickfontsize=16, legendfontsize=16) # trend line

scatter!(p1, pred, normal_obs, color=:orange, markershape=:circle, label="Normal Residuals")

scatter!(p1, pred, skewed_obs, color=:green, markershape=:square, label="Skewed Residuals")

xlabel!(p1, "Predictors")

ylabel!(p1, "Observations")

plot!(p1, size=(600, 450))

# densities of residual distributions

p2 = histogram(rand(Normal(0, 3), 1000), color=:orange, alpha=0.5, label="Normal Distribution", guidefontsize=18, tickfontsize=16, legendfontsize=16)

histogram!(p2, rand(SkewNormal(0, 3, 2), 1000), color=:green, alpha=0.5, label="SkewNormal Distribution")

xlabel!("Value")

ylabel!("Count")

plot!(p2, size=(600, 450))

display(p1)

display(p2)Fat Tails

Code

# generate normal residuals

normal_residuals = rand(Normal(0, 3), length(pred))

normal_obs = trend .+ normal_residuals

## generate fat-tailed residuals

cauchy_residuals = rand(Cauchy(0, 1), length(pred))

cauchy_obs = trend .+ cauchy_residuals

# make plots

# scatterplot of observations

p1 = plot(0:10, f.(0:10), color=:black, label="Trend Line", linewidth=2, guidefontsize=18, tickfontsize=16, legendfontsize=16) # trend line

scatter!(p1, pred, normal_obs, color=:orange, markershape=:circle, label="Normal Residuals")

scatter!(p1, pred, cauchy_obs, color=:green, markershape=:square, label="Fat-Tailed Residuals")

xlabel!(p1, "Predictors")

ylabel!(p1, "Observations")

plot!(p1, size=(600, 450))

# densities of residual distributions

p2 = histogram(rand(Normal(0, 3), 1000), color=:orange, alpha=0.5, label="Normal Distribution", guidefontsize=18, tickfontsize=16, legendfontsize=16)

histogram!(p2, rand(Cauchy(0, 1), 1000), color=:green, alpha=0.5, label="Cauchy Distribution")

xlabel!("Value")

ylabel!("Count")

plot!(p2, size=(600, 450))

xlims!(-20, 20)

display(p1)

display(p2)Quantile-Quantile (Q-Q) Plots

Particularly with small sample sizes, just staring at data can be unhelpful.

Q-Q plots are useful for checking goodness of fit of a proposed distribution.

Q-Q Plot Example

Code

## generate fat-tailed residuals

cauchy_samps = rand(Cauchy(0, 1), 20)

# make plots

# scatterplot of observations

p1 = plot(Normal(0, 2), linewidth=3, color=:green, label="Normal Distribution", yaxis=false, tickfontsize=16, guidefontsize=18, legendfontsize=18)

plot!(p1, Cauchy(0, 1), linewidth=3, color=:orange, linestyle=:dash, label="Cauchy Distribution")

xlims!(p1, (-10, 10))

xlabel!("Value")

plot!(p1, size=(500, 450))

# densities of residual distributions

p2 = qqplot(Normal, cauchy_samps, tickfontsize=16, guidefontsize=18, linewidth=3, markersize=6)

xlabel!(p2, "Theoretical Quantiles")

ylabel!(p2, "Empirical Quantiles")

plot!(p2, size=(500, 450))

display(p1)

display(p2)Predictive Checks

How well do projections match data (Gelman, 2004)?

Can be quantitative or qualitative.

Predictive Check: EBM Example

Code

# set number of sampled simulations

n_samples = 1000

residuals = rand(Normal(0, θ[end]), (n_samples, length(temp_obs)))

model_out = ebm_wrap(θ[1:end-1])

# this uses broadcasting to "sweep" the model simulation across the sampled residual matrix

model_sim = residuals .+ model_out' # need to transpose the model output vector due to how Julia treats vector dimensions

q_90 = mapslices(col -> quantile(col, [0.05, 0.95]), model_sim,; dims=1) # compute 90% prediction interval

plot(hind_years, model_out, color=:red, linewidth=3, label="Model Simulation", ribbon=(model_out .- q_90[1, :], q_90[2, :] .- model_out), fillalpha=0.3, xlabel="Year", ylabel="Temperature anomaly (°C)", guidefontsize=18, tickfontsize=16, legendfontsize=16, bottom_margin=5mm, left_margin=5mm)

scatter!(hind_years, temp_obs, color=:black, label="Data")

ylims!(-0.5, 1.2)Predictive Checks

Can also do predictive checks with summary statistics:

- Return periods

- Maximum/minimum values

- Predictions for out-of-sample data

Correlation and Auto-Correlation

What Is Correlation?

Correlation refers to whether two variables increase or decrease simultaneously.

Typically measured with Pearson’s coefficient:

\[r = \frac{\text{Cov}(X, Y)}{\sigma_X \sigma_Y} \in (-1, 1)\]

Correlation Examples

Code

# sample 1000 independent variables from a given normal distribution

sample_independent = rand(Normal(0, 1), (2, 1000))

p1 = scatter(sample_independent[1, :], sample_independent[2, :], label=:false, title="Independent Variables", tickfontsize=14, titlefontsize=18, guidefontsize=18)

xlabel!(p1, L"$x_1$")

ylabel!(p1, L"$x_2$")

plot!(p1, size=(400, 500))

# sample 1000 correlated variables, with r=0.7

sample_correlated = rand(MvNormal([0; 0], [1 0.7; 0.7 1]), 1000)

p2 = scatter(sample_correlated[1, :], sample_correlated[2, :], label=:false, title=L"Correlated ($r=0.7$)", tickfontsize=14, titlefontsize=18, guidefontsize=18)

xlabel!(p2, L"$x_1$")

ylabel!(p2, L"$x_2$")

plot!(p2, size=(400, 500))

# sample 1000 anti-correlated variables, with r=-0.7

sample_anticorrelated = rand(MvNormal([0; 0], [1 -0.7; -0.7 1]), 1000)

p3 = scatter(sample_anticorrelated[1, :], sample_anticorrelated[2, :], label=:false, title=L"Anticorrelated ($r=-0.7$)", tickfontsize=14, titlefontsize=18, guidefontsize=18)

xlabel!(p3, L"$x_1$")

ylabel!(p3, L"$x_2$")

plot!(p3, size=(400, 500))

display(p1)

display(p2)

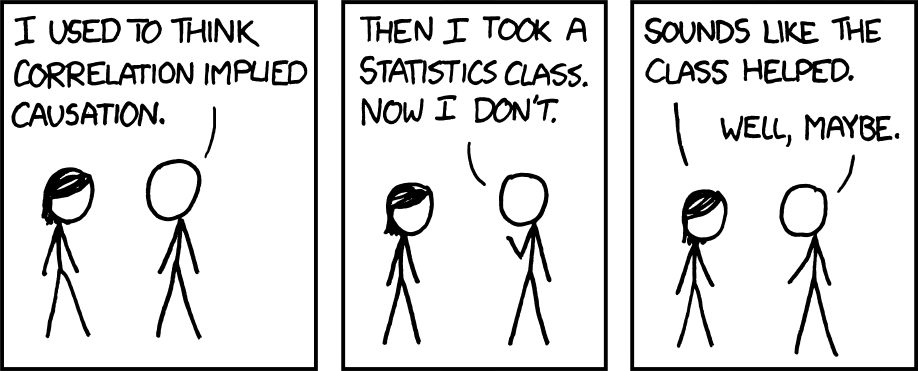

display(p3)Correlation vs. Causation

XKCD 552

Source: XKCD #552

“Correlation Does Not Imply Causation”

- Data can be correlated randomly (a spurious correlation)

- Data can be correlated due to a mutual causal factor

Spurious Correlations

Spurious Correlation Example

Source: Spurious Correlations #7602

Correlated Data Likelihood

- Marginal distributions normal: use a Multivariate Normal distribution

- Otherwise: Use copulas to “glue” marginal distributions together.

Autocorrelation

An important concept for time series is autocorrelation between \(y_t\) and \(y_{t-1}\).

Code

# sample independent series from a given normal distribution

sample_independent = rand(Normal(0, 1), 50)

p1 = plot(sample_independent, linewidth=3, ylabel=L"$y$", xlabel=L"$t$", title="Independent Series", guidefontsize=18, legend=:false, tickfontsize=16, titlefontsize=18)

plot!(p1, size=(500, 300))

# sample an autocorrelated series

sample_ar = zeros(50)

sample_ar[1] = rand(Normal(0, 1 / sqrt(1-0.6^2)))

for i = 2:50

sample_ar[i] = 0.6 * sample_ar[i-1] + rand(Normal(0, 1))

end

p2 = plot(sample_ar, linewidth=3, ylabel=L"$y$", xlabel=L"$t$", title="Autocorrelated Series", guidefontsize=18, legend=:false, tickfontsize=16, titlefontsize=18)

plot!(p2, size=(500, 300))

display(p1)

display(p2)Lagged Regression

Code

# independent samples

dat = DataFrame(Y=sample_independent[2:end], X=sample_independent[1:end-1])

fit = lm(@formula(Y~X), dat)

pred = predict(fit,dat)

p1 = scatter(sample_independent[1:end-1], sample_independent[2:end], label=:false, title="Independent Variables: r=$(round(coef(fit)[2], digits=2))", tickfontsize=16, titlefontsize=18, guidefontsize=18)

plot!(p1, dat.X, pred, linewidth=2, label=:false)

ylabel!(p1, L"$y_t$")

xlabel!(p1, L"$y_{t-1}$")

plot!(p1, size=(600, 500))

# autocorrelated

dat = DataFrame(Y=sample_ar[2:end], X=sample_ar[1:end-1])

fit = lm(@formula(Y~X), dat)

pred = predict(fit,dat)

p2 = scatter(sample_ar[1:end-1], sample_ar[2:end], label=:false, title="Autocorrelated Variables: r=$(round(coef(fit)[2], digits=2))", tickfontsize=16, titlefontsize=18, guidefontsize=18)

plot!(p2, dat.X, pred, linewidth=2, label=:false)

ylabel!(p2, L"$y_t$")

xlabel!(p2, L"$y_{t-1}$")

plot!(p2, size=(600, 500))

display(p1)

display(p2)Autocorrelation Function

Many modern programming languages have autocorrelation functions (e.g. StatsBase.autocor() in Julia) which calculates the autocorrelation at varying lags.

Autocorrelation Function

But the autocorrelation function just computes the autocorrelations at every lag. Why is this a modeling problem?

Partial Autocorrelation Function

This is solved by using the partial autocorrelation function (e.g. StatsBase.pacf()):

Autoregressive Models

An autoregressive-with-lag-\(p\) (AR(\(p\))) model: \[y_t = \sum_{i=1}^{p} \rho_i y_{t-i} + \varepsilon_t\]

Example: An AR(1) model: \[ \begin{gather*} y_t = \rho y_{t-1} + \varepsilon_t \\ \varepsilon_t \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma) \end{gather*} \]

AR(1) Likelihood

There are two ways to write down an AR(1) likelihood.

- “Whiten” the series:

\[ \begin{gather*} \varepsilon_t = y_t - y_{t-1} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma)\\ y_1 \sim \mathcal{N}\left(0, \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{1-\rho^2}}\right) \end{gather*} \]

AR(1) Likelihood

- Joint likelihood:

\[ \mathbf{y} \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \Sigma) \qquad \Sigma = \begin{pmatrix}\frac{\sigma^2}{1-\rho^2} & \rho & \rho^2 & \ldots & \rho^{T-1} \\ \rho & \frac{\sigma^2}{1-\rho^2} & \rho & \ldots & \rho^{T-2} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ \rho^{T-1} & \rho^{T-2} & \rho^{T-3} & \ldots & \frac{\sigma^2}{1-\rho^2} \end{pmatrix} \]

Model-Data Discrepancy

Model-Data Discrepancy

Model-data discrepancy: systematic disagreements between model and the modeled system state (Brynjarsdóttir & O’Hagan, 2014).

Let \(F(\mathbf{x}; \mathbf{\theta})\) be the simulation model:

- \(\mathbf{x}\) are the “control variables”;

- \(\mathbf{\theta}\) are the “calibration variables”.

Model-Data Discrepancy

If \(\mathbf{y}\) are the “observations,”” we can model these as: \[\mathbf{y} = z(\mathbf{x}) + \mathbf{\varepsilon},\] where

- \(z(\mathbf{x})\) is the “true” system state at control variable \(\mathbf{x}\);

- \(\mathbf{\varepsilon}\) are observation errors.

Model-Data Discrepancy

Then the discrepancy \(\zeta\) between the simulation and the modeled system is: \[\zeta(\mathbf{x}; \mathbf{\theta}) = z(\mathbf{x}) - F(\mathbf{x}; \mathbf{\theta}).\]

Then observations can be written as:

\[\mathbf{y} = F(\mathbf{x}; \mathbf{\theta}) + \zeta(\mathbf{x}; \mathbf{\theta}) + \mathbf{\varepsilon}.\]

Simple Discrepancy Example

Common to model observation errors as normally-distributed: \(\varepsilon_t \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \omega)\)

If the discrepancy is also i.i.d. normal: \(\zeta_t \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma)\).

Residuals: \[\zeta_t + \varepsilon_t \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sqrt{\omega^2 + \sigma^2})\]

Complex Discrepancy Example

Now suppose the discrepancy is AR(1).

\[\begin{gather*} \mathbf{\zeta} + \mathbf{\varepsilon} \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \Sigma) \\ \Sigma = \begin{pmatrix}\frac{\sigma^2}{1-\rho^2} + {\color{red}\omega^2} & \rho & \rho^2 & \ldots & \rho^{T-1} \\ \rho & \frac{\sigma^2}{1-\rho^2} + {\color{red}\omega^2} & \rho & \ldots & \rho^{T-2} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ \rho^{T-1} & \rho^{T-2} & \rho^{T-3} & \ldots & \frac{\sigma^2}{1-\rho^2} + {\color{red}\omega^2} \end{pmatrix} \end{gather*} \]

Fitting Discrepancies

In many cases, separating discrepancy from observation error is tricky without prior information about variances.

Example: \[\zeta_t + \varepsilon_t \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sqrt{\omega^2 + \sigma^2})\]

Not being able to separate \(\omega\) from \(\sigma\) is a problem called non-identifiability.

Discrepancies and Machine Learning

Can use machine learning models to “emulate” complex discrepancies and error structures.

More on ML as an emulation/error tool later in the semester.

Key Points and Upcoming Schedule

Key Points: EDA

- EDA helps identify a good or bad probability model;

- No black-box workflow: make plots, compare samples from proposed model to data, try to be skeptical

Key Points: Correlation

- Check for correlations, but think mechanistically.

- Use partial autocorrelation functions to find autoregressive model orders.

Key Points: Discrepancy

- Separate out “model bias” from observation errors.

- Often neglected: can be hard to fit without prior information on parameters.

- Use provided observation error variances when available to avoid non-identifiability.

Next Class(es)

Wednesday: Bayesian Statistics and Prior Information

Assessments

Friday: Exercise 1 due by 9pm.

HW2 assigned this week (will announce on Ed), due 2/23 by 9pm.