Uncertainty and Probability Review

Lecture 02

January 24, 2024

Last Class

Modes of Data Analysis

Workflow/Course Organization

Questions?

Text: VSRIKRISH to 22333

Uncertainty

What Is Uncertainty?

…A departure from the (unachievable) ideal of complete determinism…

— Walker et al. (2003)

Types of Uncertainty

- Aleatoric uncertainty: Uncertainties due to randomness/stochasticity;

- Epistemic uncertainty: Uncertainties due to lack of knowledge.

Data-Relevant Uncertainty Taxonomy

| Uncertainty | Associated Uncertainties | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Structural | Included physical processes, mathematical form | Model inadequacy, (epistemic) residual uncertainty |

| Parametric | Parameter uncertainty | Choice of parameters, strength of coupling between models |

| Sampling | Natural variability, (aleatoric) residual uncertainty | Internal variability, uncertain boundary conditions |

Probability Distributions

Probability Distributions

Probability distributions are often used to quantify uncertainty.

\[x \to \mathbb{P}_{\color{green}\nu}[x] = p_{\color{green}\nu}\left(x | {\color{purple}\theta}\right)\]

- \({\color{green}\nu}\): probability distribution (often implicit);

- \({\color{purple}\theta}\): distribution parameters

Sampling Notation

To write \(x\) is sampled from \(p(x|\theta)\): \[x \sim f(\theta)\]

For example, for a normal distribution: \[x \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu, \sigma)\]

Probability Density Function

A continuous distribution \(\mathcal{D}\) has a probability density function (PDF) \(f_\mathcal{D}(x) = p(x | \theta)\).

The probability of \(x\) occurring in an interval \((a, b)\) is \[\mathbb{P}[a \leq x \leq b] = \int_a^b f_\mathcal{D}(x)dx.\]

Important

The probability that \(x\) has a specific value \(x^*\), \(\mathbb{P}(x = x^*)\), is zero!

Cumulative Density Functions

If \(\mathcal{D}\) is a distribution with PDF \(f_\mathcal{D}(x)\), the cumulative density function (CDF) of \(\mathcal{D}\) \(F_\mathcal{D}(x)\):

\[F_\mathcal{D}(x) = \int_{-\infty}^x f_\mathcal{D}(u)du.\]

If \(f_\mathcal{D}\) is continuous at \(x\): \[f_\mathcal{D}(x) = \frac{d}{dx}F_\mathcal{D}(x).\]

Probability Mass Functions

Discrete distributions have probability mass functions (PMFs) which are defined at point values, e.g. \(p(x = x^*) \neq 0\).

Example: Normal Distribution

\[f_\mathcal{D}(x) = p(x | \mu, \sigma) = \frac{1}{\sigma\sqrt{2\pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{x - \mu}{\sigma}^2\right)\right)\]

Why Are Normal Distributions So Commonly Used?

- Symmetry/Unimodality

- Linearity

- Central Limit Theorem

Linearity

- If \(X \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu, \sigma)\): \[\bbox[yellow, 10px, border:5px solid red] {aX + b \sim \mathcal{N}\left(a\mu + b, |a|\sigma\right)}\]

- If \(X_1 \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_1, \sigma_1)\), \(X_2 \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_2, \sigma_2)\): \[\bbox[yellow, 5px, border:5px solid red] {X_1 + X_2 \sim \mathcal{N}\left(\mu_1 + \mu_2, \sqrt{\sigma_1^2 + \sigma_2^2}\right)}\]

Central Limit Theorem: Sampling Distributions

The sum or mean of a random sample is itself a random variable:

\[\bar{X}_n = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n X_i \sim \mathcal{D}_n\]

\(\mathcal{D}_n\): The sampling distribution of the mean (or sum, or other estimate of interest).

Central Limit Theorem

If

- \(\mathbb{E}[X_i] = \mu\)

- and \(\text{Var}(X_i) = \sigma^2 < \infty\),

\[\begin{align*} &\bbox[yellow, 10px, border:5px solid red] {\lim_{n \to \infty} \sqrt{n}(\bar{X}_n - \mu ) = \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)} \\ \Rightarrow &\bbox[yellow, 10px, border:5px solid red] {\bar{X}_n \overset{\text{approx}}{\sim} \mathcal{N}(\mu, \sigma^2/n)} \end{align*}\]

Central Limit Theorem (More Intuitive)

For a large enough set of samples, the sampling distribution of a sum or mean of random variables is approximately a normal distribution, even if the random variables themselves are not.

Why Are Normal Distributions So Commonly Used?

- Central Limit Theorem: For a large enough dataset, can assume statistical quantities have an approximately normal distribution.

- Linearity/Other Mathematical Properties: Easy to work with/do calculations

Can we think about when this might break down?

Other Useful Distributions

- Uniform: \(\text{Unif}(a, b)\) (equal probability);

- Poisson: \(\text{Poisson}(\lambda)\) (count data);

- Bernoulli: \(\text{Bernoulli}(p)\) (coin flips);

- Binomial: \(\text{Binomial}(n, p)\) (number of successes);

- Cauchy: \(\text{Cauchy}(\gamma)\) (fat tails);

- Generalized Extreme Value: \(\text{GEV}(\mu, \sigma, \xi)\) (maxima/minima)

Uncertainty and Probability

What Is Probability?

How we communicate/capture uncertainty depends on how we interpret probability:

- Frequentist: \(\mathbb{P}[A]\) is the long-run frequency of event A occurring.

- Bayesian: \(\mathbb{P}[A]\) is the degree of belief (betting odds) of event A occurring.

Frequentist Probability

Frequentist:

- Data are random, but there is a “true” parameter set for a given model.

- How consistent are estimates for different data?

Bayesian:

- Data and parameters are random;

- Probability of parameters and unobserved data as consistency with observations.

Confidence Intervals

Frequentist estimates have confidence intervals, which will contain the “true” parameter value for \(\alpha\)% of data samples.

No guarantee that an individual CI contains the true value (with any “probability”)!

Example: 95% CIs for N(0.4, 2)

Code

# set up distribution

mean_true = 0.4

n_cis = 100 # number of CIs to compute

dist = Normal(mean_true, 2)

# use sample size of 100

samples = rand(dist, (100, n_cis))

# mapslices broadcasts over a matrix dimension, could also use a loop

sample_means = mapslices(mean, samples; dims=1)

sample_sd = mapslices(std, samples; dims=1)

mc_sd = 1.96 * sample_sd / sqrt(100)

mc_ci = zeros(n_cis, 2) # preallocate

for i = 1:n_cis

mc_ci[i, 1] = sample_means[i] - mc_sd[i]

mc_ci[i, 2] = sample_means[i] + mc_sd[i]

end

# find which CIs contain the true value

ci_true = (mc_ci[:, 1] .< mean_true) .&& (mc_ci[:, 2] .> mean_true)

# compute percentage of CIs which contain the true value

ci_frac1 = 100 * sum(ci_true) ./ n_cis

# plot CIs

p1 = plot([mc_ci[1, :]], [1, 1], linewidth=3, color=:blue, label="95% Confidence Interval", title="Sample Size 100", yticks=:false, tickfontsize=14, titlefontsize=20, legend=:false, guidefontsize=16)

for i = 2:n_cis

if ci_true[i]

plot!(p1, [mc_ci[i, :]], [i, i], linewidth=2, color=:blue, label=:false)

else

plot!(p1, [mc_ci[i, :]], [i, i], linewidth=2, color=:red, label=:false)

end

end

vline!(p1, [mean_true], color=:black, linewidth=2, linestyle=:dash, label="True Value") # plot true value as a vertical line

xaxis!(p1, "Estimate")

plot!(p1, size=(500, 400)) # resize to fit slide

# use sample size of 1000

samples = rand(dist, (1000, n_cis))

# mapslices broadcasts over a matrix dimension, could also use a loop

sample_means = mapslices(mean, samples; dims=1)

sample_sd = mapslices(std, samples; dims=1)

mc_sd = 1.96 * sample_sd / sqrt(1000)

mc_ci = zeros(n_cis, 2) # preallocate

for i = 1:n_cis

mc_ci[i, 1] = sample_means[i] - mc_sd[i]

mc_ci[i, 2] = sample_means[i] + mc_sd[i]

end

# find which CIs contain the true value

ci_true = (mc_ci[:, 1] .< mean_true) .&& (mc_ci[:, 2] .> mean_true)

# compute percentage of CIs which contain the true value

ci_frac2 = 100 * sum(ci_true) ./ n_cis

# plot CIs

p2 = plot([mc_ci[1, :]], [1, 1], linewidth=3, color=:blue, label="95% Confidence Interval", title="Sample Size 1,000", yticks=:false, tickfontsize=14, titlefontsize=20, legend=:false, guidefontsize=16)

for i = 2:n_cis

if ci_true[i]

plot!(p2, [mc_ci[i, :]], [i, i], linewidth=2, color=:blue, label=:false)

else

plot!(p2, [mc_ci[i, :]], [i, i], linewidth=2, color=:red, label=:false)

end

end

vline!(p2, [mean_true], color=:black, linewidth=2, linestyle=:dash, label="True Value") # plot true value as a vertical line

xaxis!(p2, "Estimate")

plot!(p2, size=(500, 400)) # resize to fit slide

display(p1)

display(p2)90% of the CIs contain the true value (left) vs. 94% (right)

Correlations

Correlation refers to whether two variables increase or decrease simultaneously.

Typically measured with Pearson’s coefficient:

\[r = \frac{\text{Cov}(X, Y)}{\sigma_X \sigma_Y} \in (-1, 1)\]

Correlation Examples

Code

# sample 1000 independent variables from a given normal distribution

sample_independent = rand(Normal(0, 1), (2, 1000))

p1 = scatter(sample_independent[1, :], sample_independent[2, :], label=:false, title="Independent Variables", tickfontsize=14, titlefontsize=18, guidefontsize=18)

xlabel!(p1, L"$x_1$")

ylabel!(p1, L"$x_2$")

plot!(p1, size=(400, 500))

# sample 1000 correlated variables, with r=0.7

sample_correlated = rand(MvNormal([0; 0], [1 0.7; 0.7 1]), 1000)

p2 = scatter(sample_correlated[1, :], sample_correlated[2, :], label=:false, title=L"Correlated ($r=0.7$)", tickfontsize=14, titlefontsize=18, guidefontsize=18)

xlabel!(p2, L"$x_1$")

ylabel!(p2, L"$x_2$")

plot!(p2, size=(400, 500))

# sample 1000 anti-correlated variables, with r=-0.7

sample_anticorrelated = rand(MvNormal([0; 0], [1 -0.7; -0.7 1]), 1000)

p3 = scatter(sample_anticorrelated[1, :], sample_anticorrelated[2, :], label=:false, title=L"Anticorrelated ($r=-0.7$)", tickfontsize=14, titlefontsize=18, guidefontsize=18)

xlabel!(p3, L"$x_1$")

ylabel!(p3, L"$x_2$")

plot!(p3, size=(400, 500))

display(p1)

display(p2)

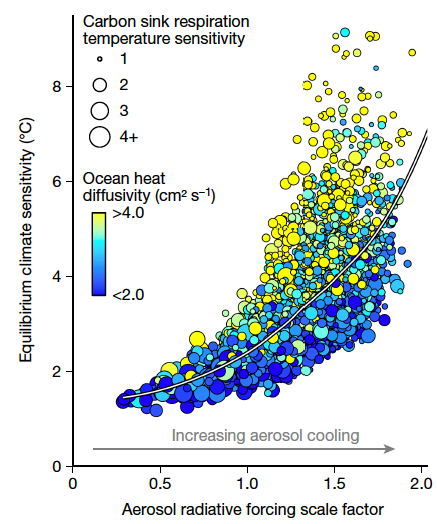

display(p3)Correlation and Climate Models

Source: Errickson et al. (2021)

Autocorrelation

Time series can also be auto-correlated, called an autoregressive model:

\[y_t = \sum_{i=1}^{t-1} \rho_i y_{t-i} + \varepsilon_t\]

Example: A time series is autocorrelated with lag 1 (called an AR(1) model) if \(y_t = \rho y_{t-1} + \varepsilon_t\).

Recap

Key Points

- Different model-relevant uncertainties (will matter later!)

- Reviewed probability distribution basics

- Many different distributions, suitable for different purposes

- Probability density functions vs. cumulative density functions

Key Points

- Frequentist vs. Bayesian probability (matters a bit later)

- Frequentist: parameters as fixed (trying to recover with enough experiments)

- Bayesian: parameters as random (probability reflects degree of consistency with observations)

- In both cases data are random!

Key Points

- Confidence Intervals:

- \(\alpha\)% of \(\alpha\)-CIs generated from different samples will contain the “true” parameter value

- Do not say anything about probability of including true value!

Key Points

- Independence vs. Correlations

- Do two variables increase/decrease together/in opposition or are they unrelated?

- Can be very important scientifically!